Vernacular architecture

County Clare is fortunate to have a wealth of vernacular structures, built for the most part during the last two centuries.

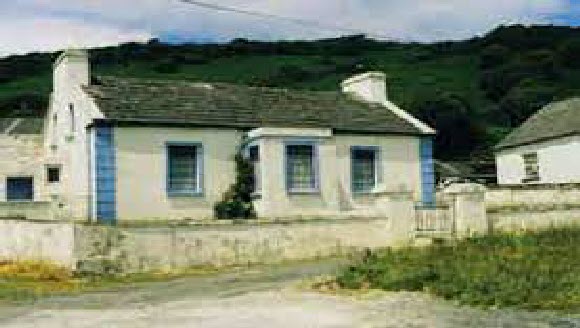

Vernacular buildings in County Clare

Vernacular buildings appeal stems from their use of natural indigenous, materials e.g., limestone and sandstone masonry, cob – a mixture of clay and straw construction, Moher and Killaloe slate roofs and wooden windows, doors etc. These materials allow such buildings to assimilate easily into the natural landscape, minimising the effects of visual impact.

Their basic simplicity and smaller scale also help to make them more attractive and sympathetic to their natural settings.

Typical examples of County Clare vernacular houses could be categorised into three main house types:

- Four or five bay, single storey, gabled, stone farmhouses with natural slate or thatched roofs and high, robust chimneys, located on gables or in the centre of the roof. These are often flanked by similar gabled out-buildings set at right angles to the main house.

- Three or four bay, two storey, gabled or hipped stone farmhouses with natural slate roofs and gable chimneys. These are more common in East Clare where the land could support the construction of a greater number of more expensive two storey farmhouses.

- One and a half storey, three or four bay, stone, gabled ended, farmhouses with stone or brick chimneys. The upper floors are generally lit by wall – head dormer windows which allow greater room in the attic spaces for bedrooms. These are generally found in East Clare where they are becoming increasingly rare.

Your Vernacular architecture

Vernacular architecture establishes a relationship between people, climate and building and powerfully reflects time, place and culture. Until very recently, it was only those at the highest rung of the economic ladder who consciously designed their homes and where architectural style played a significant role. However, surveys have shown that there are many patterns in terms of materials, positioning and functionality which relate to the lives of our ancestors at the times in which the houses were built. For example, read the following summary report Vernacular Architecture in the Doonbeg Area of West Clare [PDF,120KB].

Roofing materials, County Clare

Although straw, rush or reed thatch was predominantly used in Clare for roofing, in prehistoric times, a variety of materials became popular during the mediaeval period, particularly for castles, churches and abbeys.

Thatch

Thatch was a popular roofing material in rural areas until the 1940s and 1950s when cheaper, maintenance-free, asbestos slates became available. Over two decades the traditional roof, which had existed in the County for millennia, was almost totally replaced by the new artificial material, leaving County Clare with less thatched roofs than almost any other county in Ireland. Recent increases in the cost of fire insurance have placed the remaining thatched roofs under threat. Until the beginning of the 20th century many town and village streets contained single and two storey thatched buildings which was an old tradition going back centuries. Thomas Dineley in 1680 recalled that Ennis had only twelve slated houses, all the rest being covered in thatch. By the early 20th century only one thatched house remained in the town centre, in O'Connell Street.

In 2005, Clare County Council in partnership with The Heritage Council undertook a comprehensive audit of all vernacular and modern thatched structures in County Clare. The survey was undertaken by Carrig Conservation.Overall, 95 records were made, comprising both historic and modern thatched structures. Out of these records, 61 vernacular or historic structures were recorded. The remaining 34 records comprised modern thatched structures

Broadford slate

County Clare was fortunate and unique in having a variety of natural slates including Broadford, Killaloe and Moher, as well as other less well known slate quarries which produced poorer quality slates for local use. A local place name near Rath, Corofin refers to its former slate production i.e. “Cnoc na Slinnte”.

The quarries at Broadford produced a light greenish sandy-textured, thick slate during the mediaeval period that was extensively used on churches and castles. The museum at Dysert O’Dea houses some rare examples from the nearby Romanesque church and O’Dea’s tower house. These were hand-drilled with 12 mm holes and pegged to the roofs with oak dowels. Oak dowels were extensively used in former times, in preference to iron nails, which were susceptible to rust.

The Broadford quarries provided slate for most public buildings and country houses until the beginning of the 19th century when Killaloe slate became more popular. The quarries at Broadford are shown on the County Clare Grand Jury Map, published 1787. Buildings such as Mountshannon Market House and Broadford Glebe, which retain their Broadford roofs, are increasingly rare and most are listed in the Record of Protected Structures for County Clare.

Killaloe slate

Killaloe slates were produced at various quarries and at Portroe, County Tipperary and exported by canal barge and steamer from Killaloe during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although similar in colour and texture to Broadford slate, it can be extracted in much thinner veins, making it lighter to transport and support on a roof. Like Broadford, this slate does not suffer from weather or lamination, making it ideal for salvage and re-use. Each slate is fixed using a pair of nails. Many large public buildings such as hospitals, churches, courthouses, workhouses etc. were roofed using this material, including the Ardnacrusha Hydro-Electric Station, built in 1929. The slate was exported to Scotland in the mid 19th century and each slate was sold for one penny, hence they became known as "Penny Greens".

Moher slate

Slate from quarries between Liscannor and Doolin has been manufactured since late mediaeval times. The earliest extant evidence is from a 15th century porch on Kilmacrehy ruined church, Liscannor. Many 18th and 19th century buildings in North Clare still retain their Moher Slate roofs. Very large slates were used to roof mono pitched out buildings. ;Up to the mid 20th century practically all buildings in the towns of Miltown Malbay, Lahinch and Ennistymon were covered with this material which is fixed to the wooden laths by means of oak dowels or iron nails driven into nicks in the sides of the slates, rather than drilled holes (due to the hardness of the slate, which is not easily drilled with hand tools).

Knockerra slate

A grey narrow flagstone from Knockerra quarries near Kilrush was used as a roofing slate in West Clare during the 18th and 19th centuries. It is now very rare but still found on outbuildings and for wall capping in the Knockerra area. A bed of worked slate can also be seen close to the castle pier in Carrigaholt.

Blue bangor slate

In the late 19th century, Welsh, “Blue Bangor” slate was imported and used for the new railway and canal network, and could be purchased in every part of Ireland. This slate was cheap and light and gradually replaced local slate on buildings throughout the country. This purple-tinted, smooth-textured slate remained popular until the mid 20th century when it was replaced by the cheaper asbestos slate, corrugated asbestos and galvanised iron for roofing.

Killaloe Slate - The best-known Irish produced natural roofing slate was Killaloe from the vast slate quarries in the Arra Mountains at Portroe, near Nenagh in County Tipperary.It was exported by canal barge and steamer from Killaloe during the 19th and early 20th centuries

The future

Due to a recent reduction in the cost of imported natural slate there appears to be a change of attitude on the part of developers, architects and builders to roofing material. New imported natural quarry slate is becoming popular again and is being used on roofs, new and old, throughout County Clare. The cost of natural slate has dropped significantly due to competition and is now on a par with asbestos, cement-fibre, concrete tile or other artificially manufactured materials.

Local Authorities request natural slate is used on protected structures, architectural conservation areas, towns and villages and individual houses in scenic areas. Developers are encouraged to use sustainable, natural materials in building, once again.

Rural house design

In order to encourage appropriate consideration for house design in rural Clare, the County Clare Rural House Design Guide [PDF,3.6MB] was produced. This design guide was prepared to show the importance of good siting and sensitive design when building in the Clare countryside. Much of the unsatisfactory rural house design throughout the county has resulted from catalogue type housing, where new dwellings are randomly located on a site with no relation to orientation, aspect, site surrounds, regional characteristics and the individual needs.

Quarries in County Clare

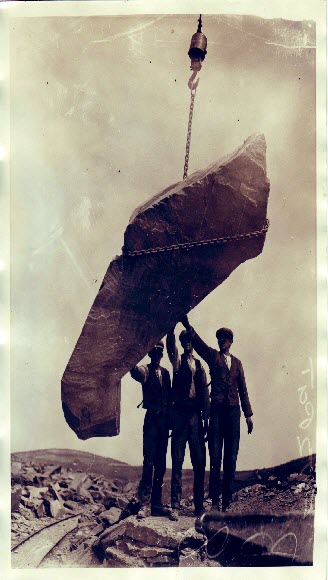

The practice of quarrying stone in County Clare stretches back over 6,000 years when the great monoliths were lifted from the limestone bedrock to construct the dolmens and portal-tombs of the Neolithic and Bronze Age Eras. During the Iron Age thousands of tons of loose stone was cleared from the surface or dug from shallow quarries to construct the numerous, circular stone forts found throughout County Clare.

The Early Christian Period to the late Mediaeval saw quarries opened up in practically every townland, to build churches, abbeys, round towers, castles and tower houses and this industry continued to expand, with time, as Georgian Houses, Bridges, Schools, Quays, Workhouses and many public works projects were completed into the twentieth century.

Slate quarries also operated from the mediaeval period, the most important being those at Doolin, Liscannor, Knockerra near Kilrush and Broadford in East Clare. These produced very high quality roofing slates during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, much of them for export to England and Scotland, where Killaloe slates were known as “Penny Greens” due to their colour and standard cost.

With the expansion of the railway systems, cheaper "Blue Bangor" slates from Wales became more popular during the late 19th century, resulting in the gradual demise of our local slate quarries. With the growing popularity of natural slate and the rising cost of oil, maybe some day our local slate quarries will again become profitable and replace the huge amount of slate presently imported from as far away as China and Brazil.

Page last reviewed: 10/03/22

Content managed by: Planning Department

Back to topContact

Áras Contae an Chláir

New Road

Ennis

Co. Clare

V95 DXP2

(065) 684 6407

Phone lines

• Open Monday – Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.

• Closed - Saturdays, Sundays and Bank Holidays Public counters

• Cash Office: Open Monday – Friday 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

• Customer Services: Open Monday – Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m

• Planning: Open Monday – Friday 9:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m

This is just for feedback on our web site, not comments or questions about our services.

To tell us about anything else, go to our contact us pages.